What makes a flood — a flood?

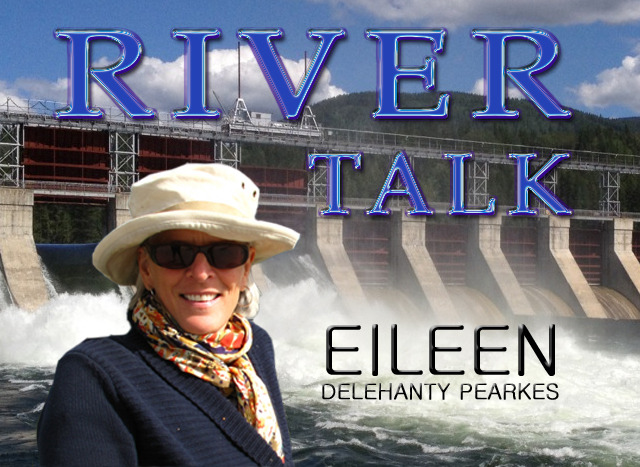

Since 2005, Eileen Delehanty Pearkes has researched and explored the natural and human history of the rivers of the upper Columbia River Basin.

She speaks frequently at conferences and symposia throughout the Basin on the history of the Columbia River Treaty and its effects on Basin residents. She has recently completed a manuscript titled A River Captured – history and hydro-electricity in the upper Columbia Basin.

An American by birth, Pearkes has been a resident of Canada since 1985 and Nelson since 1994. She has written many articles and several books that explore place and its cultural meaning.

The Geography of Memory, a history of the landscape and indigenous people of the upper Columbia watershed published in 2002, remains a Kootenay classic.

Pearkes has agreed to help The Nelson Daily readers understand the importance of the Columbia River Treaty to the region with another edition of River Talk.

Today the river historian writes about flood control.

What makes a flood, a flood?

We are approaching mid-June, so it seems like a good time to ask this question. A few years ago, a tribal leader in the U.S. gave a presentation on the importance of spring floods for the success of fish spawning. Putting up an image of a park bench that was close to being inundated, he said: Who put the park bench in the wrong place?

Once each week, B.C. Hydro sends out a reservoir operations update that summarizes the snow forecasts for this year’s spring melt and predicts water levels in the Columbia River valley for that week and the rest of the melt season.

The annual snow forecast has been determined through data collected at multiple “snow pillow” stations high in the mountains surrounding the Columbia River. It gives the hydro-engineers an idea of how much room they need to create in the reservoirs to hold the snowmelt this year.

Snow levels are only one predictor of how the flood season will unfold. The significant flood of 1948 was a year of relatively high but not epic snow pack. What really made the big flood was the weather in late May and early June. A significant spring heat wave got the snow melting.

A week of rain contributed more water to the system. By the end of the first week in June, the flood was unmanageable. Communities like Trail and Kimberley were scrambling to protect property.

In terms of snow levels, 1961 was bigger than 1948, but less flooding occurred due to a more gradual melt. There have been other “big water” years, including the most recent in 2012.

Heavy rains in June created a significant and surprising flood scenario, so much so that even with all the dams in place, hydro officials were scrambling to manage.

The geographic features that make our region so attractive to hydro-production also create the biggest challenge when it comes to spring flood. Where to put all the water in steep, narrow valleys?

Spring 2012 would have seen water levels rise far higher than they did if dams were not in place, a reminder of how much the storage and regulation provided by Duncan and Libby protect homeowners along the West Arm and Kootenay Lake who have built in the natural flood plain.

The storage provided by Arrow Lake Reservoir and Kinbasket also protects residents of the Columbia River valley from flood, but with far greater ecological harm. The storage in this valley is not just for flood control. It maximizes power production both in the U.S. and in Canada.

The 1964 CRT stipulated that the U.S. must pay Canada $64 million to provide flood control with the operation of the three ‘treaty’ dams – High Arrow (Keenleyside), Mica, and Duncan. This was a one-time payment for 60 years of service.

In September 2024, CRT operations will revert to “called upon” flood control. After that date, the U.S. must make use of its own reservoirs for flood control before calling upon Canada to help – unless a new agreement on the value of flood control is reached. If the two countries again enter into a coordinated flood control agreement, what will that look like and cost?

Recent meetings about the possible dredging of Grohman Narrows just west of Nelson indicate how much value our culture places on predictability and control of water levels. While dredging the narrows has been discussed several times in the past, the melt season of 2012 brought new impetus to the idea. Simply put, a dredged river bottom will increase capacity at the outlet of Kootenay Lake’s West Arm and allow the unnatural hydro-system to hold a little bit more water at the most critical peaks of spring melt.

Yet, at the public meetings, several of those attending shared their suspicion that the dredging was really about making more profit from the river, with flood control a convenient excuse. Others worried about how the dredging might impact a relatively healthy fishery there.

Do other options exist to manage spring high-water events, options that have not entered the mainstream conversation yet?

Next column will look at a trend in water engineering for flood control in the wake of Hurricane Sandy — with an approach that might well apply to our region.

See Column one.

See Column two.

See Column four.

See Column five.

See Column six.

See Column seven.