Would a little more tweaking make both sides happy

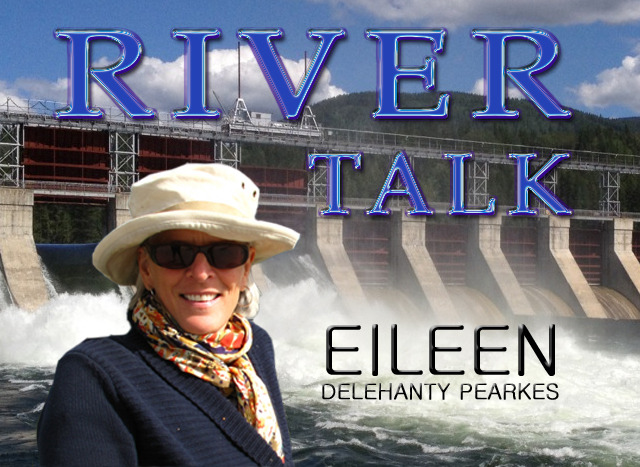

Since 2005, Eileen Delehanty Pearkes has researched and explored the natural and human history of the rivers of the upper Columbia River Basin.

She speaks frequently at conferences and symposia throughout the Basin on the history of the Columbia River Treaty and its effects on Basin residents. She has recently completed a manuscript titled A River Captured – history and hydro-electricity in the upper Columbia Basin.

An American by birth, Pearkes has been a resident of Canada since 1985 and Nelson since 1994. She has written many articles and several books that explore place and its cultural meaning.

The Geography of Memory, a history of the landscape and indigenous people of the upper Columbia watershed published in 2002, remains a Kootenay classic.

Pearkes has agreed to help The Nelson Daily readers understand the importance of the Columbia River Treaty to the region with another edition of River Talk.

As many years as I have studied the Columbia River Treaty, I can still get facts wrong. And I suppose it is the burden of expertise to confess my mistakes.

After last column was published, I was contacted by a senior B.C. government official, who offered a polite nudge regarding this statement that I had made:

“The earliest notice for changes to water management governed by the CRT would take effect in September 2024.”

While technically this statement is true with regards to a new treaty – that either country must give 10 years’ notice of intent to scrap the old treaty and negotiate a new one – and that the earliest a new treaty can begin operation is 2024 – the statement is not actually true with regards to current operations.

The CRT, signed in 1961 and ratified in 1964, has the flexibility to allow either the U.S. or Canada to make changes at any time to how water is stored and released – under mutual agreement. B.C. Hydro calls such changes to the CRT “flow agreements.”

These agreements have developed in large part as a result of the increased understanding of the negative impact of dams on resident fish in the Columbia River watershed.

A case in point is the ongoing Non-Power Use Agreement involving Canadian rainbow trout and U.S. salmon.

In 1993, both countries agreed to alter slightly the storage and release of water behind and from Hugh Keenleyside Dam. Canadian fish biologists understood that significant rainbow spawning habitat just below Keenleyside dam was being left high and dry due to discharge rates from the dam being reduced in spring, in order to fill the Arrow Reservoir.

At the same time, U.S. environmental regulations were putting pressure on dam operators below the boundary to increase flows through the system to support conditions for salmon downstream.

A compromise emerged: Canada asked to increase discharge out of Keenleyside Dam to wet the habitat for the rainbow spawners. In return, they promised to release more water from Arrow Reservoir in July and August to benefit salmon spawning below Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee Dams in the U.S.

Non-Power Use Agreements can demonstrate the spirit of goodwill that has prevailed in CRT politics in the past several decades: everyone gets something of what they want (at least if “everyone” is a government-appointed entity).

The rainbow trout Non-Power Agreement has been renewed many times since 1993. This small alteration in discharge has resulted in a improvement in conditions for rainbow trout below Hugh Keenleyside Dam.

Just ask any fisherman who likes to hang out at Tin Cup Rapids near Castlegar.

Within the over-arching, rigid structure of the CRT, small compromises are possible. More of these may be possible in the future. There are some who believe that the “CRT Review” process will ultimately result not in a whole new treaty, but only in alterations to the existing treaty.

The B.C. government’s recent announcement of its recommended 14 “tweaks” is a sign of their current approach.

Will 14 tweaks bring the CRT closer to the current, common values of our culture?

Do they answer the needs or desires of the local people?

Ah, but what are the common values?

The Columbia River is 2,000 kilometers long. It flows through several ecosystem types, states, municipalities. Water is used for irrigation, power production and fish habitat projects.

What would a river reflecting common values look like?

Do the interests of non-human residents of the Basin such as salmon hold more or less weight than the interests of power producers, industry and other human desires?

The architects of the 1964 CRT may not have had any idea how complicated it could become to manage a large river system. How many balance points can a river system hold?

What is the capacity of our political and social structures to negotiate and collectively manage a more and more intricate series of trade offs: rainbow for salmon; fewer kilowatts for increased irrigation; more riparian for less flood control.

A natural river just flows. A tightly managed river cannot be so lucky. It’s tough being in charge of an ecosystem. We must weigh and balance the impact that decisions on one part of the river will have on other parts of the river.

The intricate play of human interests will only become more apparent as the discussions over its management continue.

See Column one.

See Column two.

See Column four.