General Andrew MacNaughton a champion of CRT downstream benefits

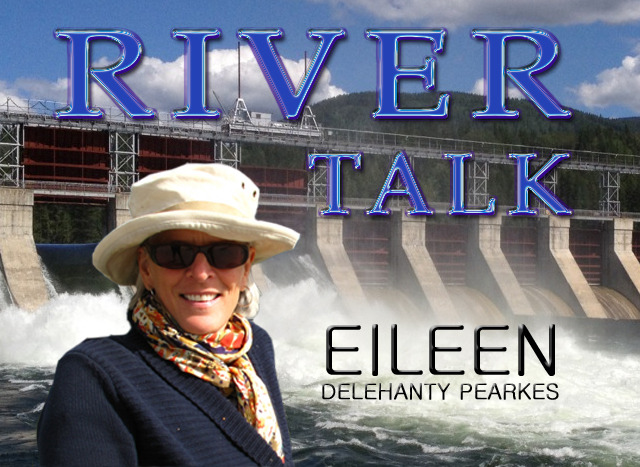

Since 2005, Eileen Delehanty Pearkes has researched and explored the natural and human history of the rivers of the upper Columbia River Basin.

She speaks frequently at conferences and symposia throughout the Basin on the history of the Columbia River Treaty and its effects on Basin residents. She has recently completed a manuscript titled A River Captured – history and hydro-electricity in the upper Columbia Basin.

An American by birth, Pearkes has been a resident of Canada since 1985 and Nelson since 1994. She has written many articles and several books that explore place and its cultural meaning.

The Geography of Memory, a history of the landscape and indigenous people of the upper Columbia watershed published in 2002, remains a Kootenay classic.

Pearkes has agreed to help The Nelson Daily readers understand the importance of the Columbia River Treaty to the region with another edition of River Talk.

In River Talk’s previous two columns, I described how the upper Columbia River watershed in Canada helps to define the whole river as a ‘snow-charged’ hydrologic system. The 1948 Flood increased a sense of urgency about these natural high water events. Both countries wanting rivers controlled and managed for human industrial and agricultural interests. Products of their time and culture, they gave little thought to ecosystems.

Informal talks began through a bi-national organization called the International Joint Commission (IJC), an agency formed by the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty. This small group of engineers had actually started talking before WWII was over. Post-flood, they had a new imperative.

In the early 1950s, Americans proposed building Libby Dam on the Kootenay River in Idaho. Not long after that, Kaiser Aluminum in the U.S. approached the B.C. government about constructing a “low dam” near Castlegar, B.C., essentially to store water to enhance electricity production for Kaiser’s plant in the U.S. This would involve flooding the Arrow Lakes valley up to the natural high water mark of the average June flood. The newly-elected B.C. Premier, W.A.C. Bennett, liked the idea. The Americans would build the dam, and B.C. would get a share of the benefits in access to low-cost power.

One Canadian member of the IJC, General Andrew MacNaughton was a fierce nationalist and didn’t like the idea of American dams controlling “Canadian” rivers. He was dead against the Libby project. Much to W.A.C. Bennett’s annoyance, the talks with Kaiser Aluminum also began to break down, due in part to a developing power struggle between his province and the Canadian feds.

Americans continued to propose Libby Dam. More than once, MacNaughton vetoed it. He came up with an idea that eventually became a central principle of the 1964 CRT: downstream benefits. Canada might consider approving a dam such as Libby, he said, if Canada somehow benefited. Furthermore, MacNaughton postured, if Canada wasn’t going to be promised some of the benefit from Libby, well then, the geography of the upper Columbia watershed would simply have to be rearranged.

MacNaughton began to speak openly about a plan to divert the water of the Kootenay River across Canal Flats into the Columbia. And while they were at it, he said, they could just divert the Columbia into the Fraser by blasting a tunnel through a few mountains, thereby keeping the aquatic riches of the Columbia system entirely in Canada.

It was a bold idea. Or was it a threat? MacNaughton believed in Canada’s sovereign use of its own resources, and his insistence stood the legal test. By the late 1950s, it was clear that Canada could divert Kootenay River water. And so it was that Americans ended up pressing for another important principle of the 1964 CRT: the control of Canada’s right to divert.

By the time the CRT was approved, each country had secured some gains. Canada had entitlement to a share of downstream benefits and the U.S. had protection against Canada’s inherent right to divert. The CRT also gave the U.S. the option to construct Libby Dam. The treaty paid Canada a 30-year lump-sum payment of the downstream benefits totaling over $350 million. This was enough, W.A.C. Bennett thought, to finance the construction of the three Canadian dams that were part of the CRT template: a by now “high” dam near Castlegar that would displace thousands of Canadians, one on the Duncan River, and one at the Big Bend of the Columbia 135 K. north of Revelstoke.

Not everyone was happy. Those living in the Arrow Lakes, Duncan and Big Bend valleys had been told that their farms and towns and trap lines and fishing grounds stood in the way of progress. Progress in 1964 meant only one thing to the government: water exchanged for money. The people (and non-human residents) of the region would just have to accept that.

See previous column two.

See previous column one.