The Salmon Speak

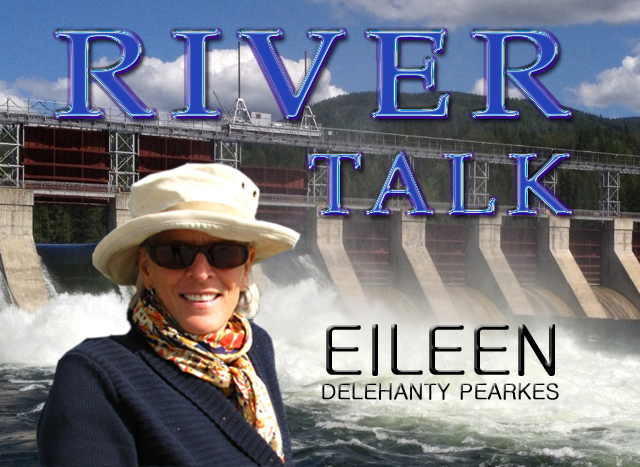

Since 2005, Eileen Delehanty Pearkes has researched and explored the natural and human history of the rivers of the upper Columbia River Basin.

She speaks frequently at conferences and symposia throughout the Basin on the history of the Columbia River Treaty and its effects on Basin residents. She has recently completed a manuscript titled A River Captured – history and hydro-electricity in the upper Columbia Basin.

An American by birth, Pearkes has been a resident of Canada since 1985 and Nelson since 1994. She has written many articles and several books that explore place and its cultural meaning.

The Geography of Memory, a history of the landscape and indigenous people of the upper Columbia watershed published in 2002, remains a Kootenay classic.

Pearkes has agreed to help The Nelson Daily readers understand the importance of the Columbia River Treaty to the region with another edition of River Talk.

Today the river historian talks about how decline of the salmon.

River Talk has been quiet for several weeks, not for lack of something to say about the CRT, but simply due to an explosion of activity south of the 49th parallel related to what is becoming known in Treaty-geek circles as the “ecosystem function.”

As a writer, researcher and speaker, I have been engaged lately in some trans-boundary work to support the understanding of the Columbia River system as one unified place.

Consider for a moment the emerging metaphor in the CRT debate of the treaty being a stool. The 1964 agreement focused on maximizing power generation and controlling flood in agricultural and urban areas: a two-legged stool.

Over the past 50 years, the lack of stability in this design has become more and more apparent, leading to a focused effort by a coalition of American tribes living along the Columbia to bring attention to a third leg – that of ecosystem function. In large part, the coalition has spoken up about the need to restore more natural flows for salmon health on lower reaches of the Columbia, and to bring ocean salmon back above Grand Coulee dam into Canadian waters.

To that end, this coalition of tribes formed in 2009 hosted a conference in Portland, Oregon on April. 23-24. They called it Future of Our Salmon: restoring historical fish passage. This is their effort to ‘get out in front’ — to press for their values to be heard as discussions continue about the way to re-shape a treaty for the 21st century. In 2011 these tribes reached out to Canadian First Nations. Representatives of several from our region attended the conference.

Paul Lumley, of Yakama descent and the Executive Director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission based in Portland, spoke early in the conference about the precipitous decline of salmon on the Columbia, employing a graph that looked like a hockey stick, with the stick hitting the ice and bending lateral at about 1940 – near the completion of Grand Coulee Dam.

It turns out that the upper watershed possesses a high and concentrated amount of spawning streams for sockeye and Chinook, as well as ‘nursery’ lakes for sockeye.

Joel Moffat from the Nez Perce tribe spoke of salmon as a “sacred resource,” describing how his people’s oral tradition has given them strength to carry on despite the loss to many Columbia Basin tributaries of this important food source.

Leon Louis of the Okanagan Nation Alliance commented: “We take and take and take. What do we give back to Mother Earth?”

Will Warnock, a biologist with the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission based in Kimberly, B.C. spoke of the high biomass of salmon that once swam 2000 kilometres to the headwaters of the Columbia in the Rocky Mountain Trench, and of the cascading effects of the loss of this keystone species to the health of the entire ecosystem.

The conference discussed frankly the many obstacles to engineering the return of salmon above Grand Coulee dam: large water fluctuations in the Arrow Lakes storage reservoir, lack of fish passage at any Canadian dam and the presence of many introduced predator fish in Grand Coulee’s Lake Roosevelt reservoir.

And yet, most tribal members in attendance did not seem to be deterred by the obstacles. Instead, they concentrated on hope and certainty. At the conclusion of the conference, Yakama elder Gerald Lewis lead a closing prayer, sung in the manner and language of his people. Before doing so, he called up all the elected and appointed leaders from the many tribes and First Nations in attendance.

Across the front of the room stretched a coalition of indigenous people whose numbers are increasing and resolve rising.

The song lead by Gerald and sung by many of the Indian people around him seemed to rise up out of the ground itself. I listened with a growing sense that it’s no longer a question “if” ocean salmon will again find passage above the dams, but “when.”

Stay tuned for next column, a look at the dynamics of spring flood.

See Column one.

See Column two.

See Column four.

See Column five.

See Column six.