Treaty talks for assured flood control have impacts in Nelson and area: province

Time may be expiring on the Columbia River Treaty but a stream of issues to continue workability between Canada and the U.S. won’t be water under the bridge just yet.

Sixty years of Assured Flood Control is set to expire in 2024 but the two countries have been in talks to modernize the historical transboundary agreement since May 2018, covering a range of topics over the course of 10 rounds of meetings.

The key areas of interest are flood risk management, hydroelectric power and ecosystems, while Canada has also raised the issues of increasing co-ordination of Libby Dam operations and increasing flexibility for Canadian operations.

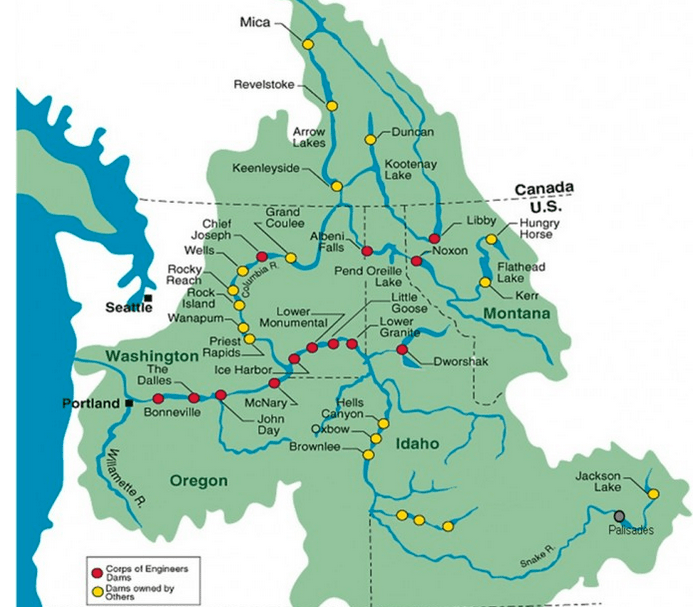

The treaty — which governs the timing and volume of water that passes through the Mica, Duncan and Hugh Keenleyside dams to prevent damaging floods and enhances hydroelectric power generation — means Canada operates with reserved space in its treaty reservoirs to reduce flood risk in the United States, but it also has ramifications in Nelson and area.

“People in the West Kootenay witness these operations as water levels fluctuate along Arrow Lakes and Duncan reservoirs and Kootenay Lake,” said Kathy Eichenberger, executive director of the provincial Columbia River Treaty team and B.C.’s lead on the Canadian Columbia River Treaty negotiation delegation.

“While there are impacts associated with those fluctuations, the treaty has enabled local GHG-free power generation along the Kootenay Canal and mitigated flooding on Kootenay Lake and below the confluence of the Columbia and Kootenay rivers in Castlegar, Genelle and Trail.”

The treaty also manages water level at certain times of the year to target fish populations in both countries for whitefish and rainbow trout (Canada) and salmon (U.S.).

The discussions between the two countries are expected to modernize the treaty in a way that could lead to a shift in when and how much water is released from the Canadian reservoirs to address ecosystem and support objectives for Indigenous cultural values and socioeconomic interests, said Eichenberger, but still provide flood risk management and power generation.

“Additional flexibility would also allow Canadian operations to adapt to future unknowns, such as the effects of climate change,” she said.

Although she could not say what stage the negotiations were at, Eichenberger said the Canadian and U.S. teams were respectful and were “truly working in good faith to come to an agreement on a modernized treaty that creates benefits for both countries and shares them equitably.”

There has been plenty of societal and ecological change since the first agreement was signed in 1964, she noted, and that has to be reflected in the new agreement, along with Basin local government and citizen input.

“While the details of negotiations are confidential, we can say that a challenge in these discussions is how to adjust to these new realities, as well as look into the medium and long term future,” said Eichenberger.

“And always considering the fundamental principle of the treaty to create benefits for both countries and share them equitably.”

There is no deadline for negotiations or requirement for how many rounds will be involved.

“The province has committed to engaging with the people in the basin before a final agreement is reached, so residents can clearly understand what the modernized treaty being proposed will contain,” said Eichenberger.

“There is currently no timeline for when that will happen; however, we will communicate it broadly once that time has been set.”

Calling upon

When the treaty expires in 2024, if a new one is not struck to replace it that could trigger a more impromptu “called upon” regime, which would require the U.S. to make “effective use” of their reservoirs to manage flood risk, drafting them more deeply and frequently, before “calling upon” Canada for additional storage to prevent damaging floods.

This is not ideal for the U.S. and also impacts B.C., said Eichenberger.

“The Canadian and U.S. negotiating teams are discussing different concepts for potentially providing some form of assured flood risk management that meets the needs of both countries,” she said. “Coordinated operations for power generation are also part of these discussions.”

On the Canadian side more flexibility is being sought in the treaty for domestic operations to meet Basin interests in areas such as ecosystem enhancement, Indigenous cultural values and socioeconomic objectives.

“Exploring mechanisms for achieving ecosystem objectives refers to the significant work being led by Canadian Basin Indigenous Nations, in collaboration with federal and provincial agencies and consultants, to determine what type of operation is needed to support healthy ecosystems,” said Eichenberger.

Latest negotiation

Canada and the U.S. met for the 12th round of negotiations to modernize the Columbia River Treaty on Jan. 10.

Building on discussions that occurred during the previous round in December 2021, the one-day virtual session focused on evolving concepts for post-2024 flood risk management, Canada’s desire for more operational flexibility, and mechanisms for achieving ecosystem objectives.

At round of negotiations in June 2020, Canada tabled a proposal outlining a framework for a modernized treaty, developed collaboratively by Canada, B.C. and Columbia Basin Indigenous Nations.

The Canadian negotiating team, which includes representatives from the governments of Canada, B.C. and the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc and Syilx Okanagan Nations, continues its collaboration on activities that are informing these historic discussions.

• The next round of negotiations will take place in the near future. Read the Information Bulletin here: https://news.gov.bc.ca/26077

• To learn more about the Columbia River Treaty: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/columbiarivertreaty/