Daily Dose — Lessons Learned from Honouring 215 Lives

Last week, we were delivered tragic news about Indigenous children who lost their lives in our province’s residential school system. Indigenous communities were hit especially hard by this discovery.

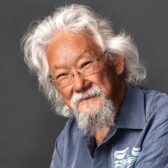

Christopher Yates, a Director of the West Kootenay Métis Society and Lesley Garlow, Indigenous Educator at Touchstones Museum, organized a memorial and ceremony for the 215 Kamloops Indian Residential School children that never made it home to their families.

Yates put out a call for children’s shoe donations for the event held on June 3rd.

This news is hitting home hard for Yates as residential schools directly impacted his family. His grandfather, grandmother, and great-grandfather all went to residential school.

“It was emotional for everybody, and throughout the week as we were setting up the memorial and ceremony, we had so many people stop by and acknowledge what was happening, what had happened and just to talk or to cry,” says Yates.

The event was held at 2:15 to signify the number of children found in the unmarked grave.

Yates explains the meaning of the lined-up shoes.

“This signifies our children lining up throughout their lifetime at school. They line up to go into the school. They line up to go home. The shoes at the start signify the children going to school tightly as many children went to residential schools. At the end of the loop, the line-up loosens to half the children’s, signifying only half returning home. At the end of the shoes returning home, the circle stops signifying an end. Those children will get no more days to line up. They never made it home from school.”

There were around 70 people safely socially distanced at the event held at Nelson’s Touchstones Museum.

“We had them move into a large circle because in Indigenous teachings, in a circle, we’re all equal. Lesley Garlow went around and smudged while I drummed the heartbeat of mother earth and walked around with a few others in attendance were drumming throughout the crowd,” says Yates.

Shoes interspersed with red dresses signified missing and murdered Indigenous women who could undoubtedly be relations of the children that died, explains Yates.

“It was powerful. The wind came up, and the red dresses were blowing. I mean, the wind really, really came up when we were drumming and smudging, to the point that the sage actually took fire. Lesley had to put it out because of the wind. It was a really neat, very powerful thing to happen at that moment.”

For the most part, Yatesand his team have felt supported by the community in running this event.

“Acknowledgement is huge. It wasn’t just Indigenous people coming by to acknowledge. The general population of Nelson came by to acknowledge the hurt and everything that’s happened. There seems to be a greater understanding that this is only the first of many residential schools where this will be found out.”

Yates received messages from non-Indigenous people asking, “How can I be a better ally to Indigenous peoples?” Being an ally means supporting the healing, reconciliation, and reparations of Indigenous communities. It means settlers acknowledging their own role in this system of harm, in operation since first European contact in North America.

Yates says the best thing allies can do is ask Indigenous communities what is needed.

“Ask them what they need for help.”

Flags in the City Hall courtyard were flying at half mast following tragic news about Indigenous children who lost their lives at the Kamloops residential school. —Submitted

Yates believes this tragic discovery is making it harder for people to deny the impact of residential schools.

“It’s changing the way some people see reconciliation. There’s still a lot of work to be done. We need to look at the 94 recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It gives us a starting point on how we as humans can make the change happen that’s needed.”

Christopher says that COVID has highly affected the way that Indigenous communities come together.

“It’s been so tough for us not to be able to engage in a physical way. COVID has shut that down and made it very difficult for us to be active in our communities. As a Métis leader, it’s hard for me to engage through online resources. We’re looking forward to this opening coming in July so we can engage our community, our allies, our people who want to engage with us.”

Yates requests non-Indigenous community members who want to partake in Indigenous events bring only good intentions.

“We don’t want people to come and argue. We want people to come with the intent of goodwill, and we welcome all people equally.”

The memorial stayed up for 24 hours. Afterwards, children in the three shelters in our area for women survivors of domestic violence will wear these shoes.

Yates acknowledges that there is so much work to be done.

“The more people understand, the more acknowledgment there is, the further and faster we’re going to move along.”

Yates extends thanks to the community for their shoe donations and participation in this event. Kinanâskomitin is Plains Cree and means Thank you, I am grateful to you. And Maarsii is Michif, the language of the Metis and means Thank You. Christopher, Maarsii, for creating this event and for sharing this story.