Can the CRT Make a ‘Normal’ River?

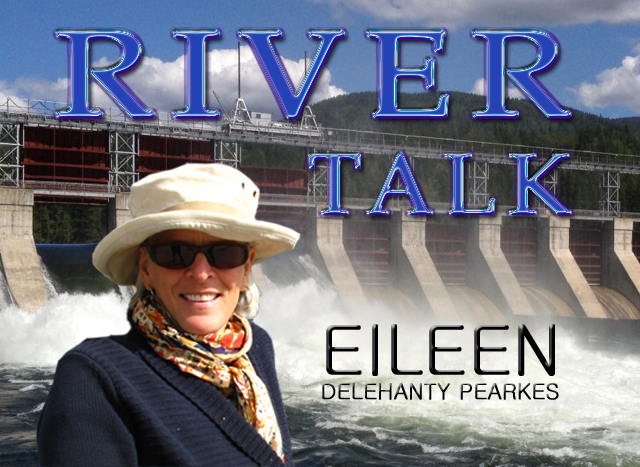

Since 2005, Eileen Delehanty Pearkes has researched and explored the natural and human history of the rivers of the upper Columbia River Basin.

She speaks frequently at conferences and symposia throughout the Basin on the history of the Columbia River Treaty and its effects on Basin residents. She has recently completed a manuscript titled A River Captured – history and hydro-electricity in the upper Columbia Basin.

An American by birth, Pearkes has been a resident of Canada since 1985 and Nelson since 1994. She has written many articles and several books that explore place and its cultural meaning.

The Geography of Memory, a history of the landscape and indigenous people of the upper Columbia watershed published in 2002, remains a Kootenay classic.

Pearkes has agreed to help The Nelson Daily readers understand the importance of the Columbia River Treaty to the region with another edition of River Talk.

Today the Pearkes writes about what is considered to be “Normal” in the Columbia Basin.

Winter has come early in the upper Columbia Basin and with it begin the annual predictions about how this year’s precipitation and temperatures will unfold.

No one really knows, but climatologists have gotten pretty good at predicting. While much of Canada is predicted to be in the deep freeze, southern B.C. looks to be near normal in terms of temperature and moisture.

Of course everyone knows that ‘normal’ is a slippery concept. As human beings, we have a strong leaning toward keeping things in the range of what we know. Normal means safety. And predictability. In the case of the Columbia River watershed, predictability equals manageability.

The Columbia River system of water management takes a show-charged system with an annual high surge of water and normalizes it – evens out that spring surge – in an effort to create what hydro-engineers call “reliable” power.

Every time you turn on a light in the Pacific Northwest, you engage with this remarkable cultural achievement: reliable, relatively inexpensive electricity created from water flowing downhill to the sea.

We have the Columbia River watershed to thank for that.

In an effort to manage the river for power production, the Columbia has been studied and measured to within an inch of its life. One extremely important annual measurement is the Columbia’s annual discharge rate as measured at The Dalles, Oregon.

This rate measures runoff through a “water year” that begins not on January 1, but on October 1 – at the advent of winter precipitation.

Scanning a list of runoff rates for water years from 1967 (the completion of Duncan Dam and near completion of Hugh Keenleyside Dam) to 2012, I see a wide variation above and below the calculation for “normal.”

Readings in 1974 and 1997 are at the high end with 146% and 148% of normal while in 1977 and 2001 are at the low end with 50% and 54% of normal.

In between these extreme years of low and high runoff, the Columbia River’s total runoff dances back and forth, proving only that it is not in any way a reliable machine.

Predictions for the annual runoff are important. They help water managers prepare for the coming year and forecast a measure of control and stability over a system that is, ultimately, at the whims of the natural world. For example, the Columbia Basin Bulletin in 2003 predicted a runoff of 70% of normal. The actual runoff was 82%. (Check out this link for more information.)

Often, predictions are within range. Sometimes they are wildly off the mark. That’s nature for you.

Climate change models are being generated and studied by many agencies in order to predict how the Columbia River’s hydrology will adapt. The CBT has produced an excellent survey report on this subject.

Across the trans-boundary Basin, things are looking dryer and warmer, especially in the mid-basin, and even more especially in the Snake River basin. The Snake is the largest of the Columbia’s many tributaries, followed by the Kootenay and the Pend d’Oreille.

Up in the wet Columbia Mountains at the top of the watershed, things are looking warmer but not necessarily dryer. A slight increase in temperature lengthens the shoulder seasons, which at higher elevations could mean continued accumulation of snow up high even as valley bottoms experience extended autumn and spring.

Warmer summers could mean more rapid snow melt and accelerated loss of exposed glaciers. This could mean lower summer flows in our rivers.

All of these studies are, at this point predictions. We really can’t know where this is all going. The variations in the flow chart from 1967 to the present demonstrate only the ongoing unpredictability of a river system that we rely on in so many ways.

As the Columbia watershed has been more and more tightly managed over the past 50-odd years since the CRT was signed, as residents of the Basin, our own expectations on the agencies who manage and control this system have increased. We want electricity at all hours of the day and night.

We don’t want a flooding river to damage our property.

We want fish.

And don’t forget. We want normal.

See Previous Column regarding the Hugh Keenleyside Dam.

See Previous Column.

See Previous Column.