Great Blue Herons: Declining population in need of strong stewardship

Story by Nicole Trigg, Kootenay Conservation Program

To many in the Kootenays, catching sight of a Great Blue Heron is a special experience.

Whether you’re standing at a river’s edge, or on the shoreline of a lake, it’s a treat to spot one nearby, either standing peacefully in the shallow water or gracefully flying by overhead.

When you do, it is reason to pause and notice their long legs, broad wings and outstretched necks.

Great Blue Herons are very large, elegant-looking birds that grow to over a metre in height. Their size combined with their simple yet bold colouring (blue-grey body feathers, white neck plumes and head, with prominent black eye stripe and yellow bill) make for an arresting image. It’s no wonder they’re considered the iconic species of wetland ecosystems.

Two heron subspecies occur in B.C. and both are provincially blue-listed because of habitat loss and disturbance in prime breeding and wintering areas. The coastal subspecies is also federally listed of Special Concern and remains there year-around, whereas interior herons either migrate or overwinter near ice-free water bodies.

Herons breed within a kilometre of slow-moving rivers, lakes and wetlands with rich food sources, often in colonies (known as heronries or rookeries), but occasionally as single pairs. Herons need big trees to support the stick nests they build, and older deciduous and coniferous stands buffered from disturbance are preferred. Herons are sensitive, and human activity and Bald Eagle harassment and predation result in nest abandonment and/or low productivity.

Kootenay-based biologist Marlene Machmer of Pandion Ecological Research has been studying Great Blue Herons in the Columbia Basin since 2002 and has witnessed a dramatic decline in the numbers of active and successful nests.

“By 2017, numbers of active heron nests were down to less than half of the 354 nests I counted back in 2002,” said Machmer. “Many areas with historical breeding were no longer active, and average colony size in active heronries plunged to single digits for the first time ever.”

Machmer’s focus has been on Great Blue Heron breeding and overwintering habitat in the Columbia Basin, where reservoir flooding, water level regulation, forest harvesting, habitat clearing for development and recreational activities have contributed to degradation and disturbance in key wetland and riparian habitats for herons.

Ironically, even in areas set aside for conservation, herons fall victim to raids on their nests by American Crows, Common Ravens and increasing numbers of Bald Eagles, or to nest site competition with Double-Crested Cormorants, all of which are impacting their reproductive success.

As part of the Kootenay Conservation Program (KCP)’s Kootenay Connect project, Machmer focused her research in 2020 in the four focal areas of the Kootenay Connect project: the Columbia Wetlands Wildlife Management Area, the Wycliffe Wildlife Corridor in the East Kootenay, the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area, and the Bonanza Biodiversity Corridor in the Slocan Valley of the West Kootenay.

KCP, in partnership with many organizations, received federal Environment and Climate Change Canada funding for Kootenay Connect, which focuses on species at risk in these four areas. These areas represent only a subset of the larger Basin-wide study area Machmer surveyed for Great Blue Herons in 2017.

As part of the 2020 survey, 18 heron breeding sites were surveyed, of which 11 heron breeding sites (with 181 nests) were confirmed occupied.

Seven of these (with 161 active nests) overlapped with the Kootenay Connect focal areas (i.e., two in the Creston Valley, four in the Columbia Wetlands, one in the Wycliffe Corridor). Considering just these areas, 1 of 7 (14.3%) sites and 66 of 161 nests (41%) failed to produce young. Nest failures were related to eagle and corvid harassment and predation, coupled with nest site competition from cormorants and disturbance due to nearby human activity.

Notably, the Bonanza Corridor area had no evidence of heron breeding activity in 2020, despite previous nesting and evidence of fledgling success four years ago. However there has been a noticeable increase in forest development in recent years, coupled with increased land and recreational developments, all of which can contribute to disturbance and displacement.

“The absence of heron breeding activity is a concern, given the abundance of suitable nesting and foraging habitat,” said Machmer.

As follow-up to the 2020 survey, heron stewardship brochures were distributed to private landowners, land managers and neighbours located near the breeding sites to promote awareness, reduce human disturbance, and encourage reporting of disturbance.

Great Blue Herons, their nests, and eggs are protected by the British Columbia Wildlife Act, the federal Migratory Birds Convention Act, and the Kootenay Boundary Wildlife Habitat Features Order. Their nest trees are also protected year-round on both public and private land, and land managers are encouraged to protect nearby riparian and wetland areas important for feeding.

“Herons are sensitive indicators of intact freshwater ecosystems,” Machmer said. “Their population declines are very concerning and underscore the need for more conservation and stewardship directed at this provincially blue-listed sub-species.”

One objective of Kootenay Connect is to conserve key habitats of listed species. An active heron breeding area located on Crown land overlooking the Columbia Wetlands Management Area south of Nicholson was proposed as a provincial Wildlife Habitat Areas (WHA), which would limit most activities that could negatively impact this critical habitat.

This site has been re-occupied for many years with 14 active heron nests in 2020, surrounded by undisturbed older forest and pocket wetlands used by a range of species.

“Herons are being progressively squeezed out of traditional breeding and overwintering areas, due to the shrinking land base of suitable habitat, coupled with increasing human encroachment and development,” Machmer said.

“People can do their part by giving herons a wide berth, being vigilant, and promptly reporting disturbance around nesting and roosting sites.”

To learn more, contact Machmer at mmachmer@netidea.com or 250-505-9978.

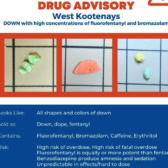

Photo Caption: Kootenay-based biologist Marlene Machmer of Pandion Ecological Research has been studying Great Blue Herons in the Columbia Basin since 2002 and has witnessed a dramatic decline in the numbers of active and successful nests. — Photo courtesy Phil Payne